Documentary Games & the Life and Death of the Saga Song

Originally written for Bogost’s News Games blog.

In looking for proof-of-concepts for the success and creation of documentary and editorial games, I came across a historical movement in country music that I think bears exploration. Country music became popular music in the United States after World War II, because so many training camps were located in the South. Soldiers from around the country were introduced to the genre then, and they brought it home with them when they returned from war. An accompanying reason for the meteoric rise of country music was the “saga song” – a prominent sub-genre in the 40’s and 50’s that openly explored tragedies such as war and murder.

Preceding the wide popularity of country music was a ballad about the “Wreck of the Old 97.” The engineer, Steve Broadey, had to make up for a one-hour delay in the delivery of a Fast Mail shipment for the USPS by traveling at unsafe speeds between Monroe and Spencer. Broadey lost control of the engine while descending a gradient toward the Stillhouse Trestle; he de-railed the train, which fell into the Cherrystone Creek ravine killing all nine passengers. Broadey was blamed for the tragedy, but as a contributor to the Wikipedia article on the song explains:

{The ballad clearly places the blame for the wreck on the railroad company for pressuring Steve Broadey to exceed a safe speed limit, for the lyrics begin, “Well, they handed him his orders in Monroe, Virginia, saying, ‘Steve, you’re way behind time; this is not 38 it is Old 97, you must put her into Spencer on time.’” }

From the point of view of editorial, this is a case of the songwriter including information that determines an editorial line: Southern Railway caused the accident by enforcing reckless driving in order to satisfy their contract with USPS.

Nashville Skyline, a column for CMT News by Chet Flippo, discusses the saga song in connection to a recently-released compilation titled “People Take Warning! Murder Ballads & Disaster Songs 1913-1938.” Flippo goes through a short history of the sub-genre before editorializing on the disappearance of the saga song in contemporary country music. He seems particularly interested in understanding why country music has shied away from addressing the Iraq War directly.

I asked the only “expert” on country music I knew, Dirt Roads and Honkeytonks DJ Sarah Fox, this same question. She explained to me that country music as we now know it is closer in spirit to pop music than to blues as a result of the manufacturing of pop during the 70s and 80s. This makes sense, in that this era also buried the protest songs of the 60s under heaps of mind-numbing disco beats and escapist love songs; however, it doesn’t explain why a popular sub-genre such as the saga song all of a sudden became un-popular. This, it would seem, is simply a natural result of the eternal shake-up of the music industry that comes with every new generation of music listeners and purchasers.

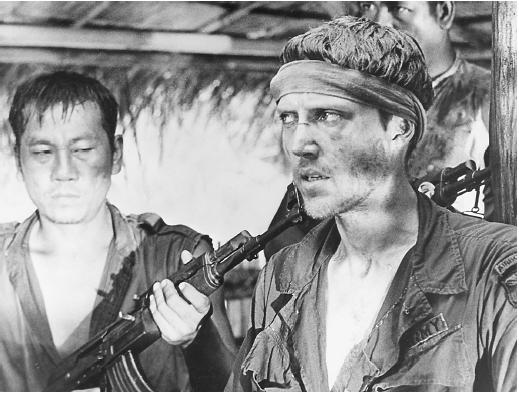

Does this mean that popular art addressing social issues is “out” across all media, and that the goals of editorial games will never reach fruition in this generation? I’d like to suggest that perhaps the issue here is simply a shifting of expectations in consumers of various media. For instance, in the film industry “war” and “issues” movies are still released in droves each year. To name a few recent ones, we can see how Syriana, Jarhead, and Lamb & Lion continue this tradition. Instead of turning on our radios to hear songs about the news, we’re going to theaters to watch movies about them. As it turns out, the decline of saga songs in the 70s and 80s roughly coincides with the emergence of the New Hollywood period in American cinema. Cimino’s Deer Hunter (1978) effectively replaces the anti-Vietnam songs of the late 60’s.

This leads me to tentatively conclude that as a medium becomes the primary vehicle through which ideas are transmitted, the popularity of editorializing artifacts in that medium rises. We can see how, in general, both the American and gaming publics are not entirely ready for political or editorial games because movies are still our primary expressive medium (despite losing ground to the games industry each year). Tracy Fullerton cites an example of this preferential reception of the dominant medium when she discusses the backlash against JFK Reloaded. The game does something that movies cannot: based on physics and a 3D space, it shows just how hard it would have been for Oswald to have fired all the shots on Kennedy’s limo. Despite this unique experience it provided, popular backlash against the game found it exploitative. Fullerton asks the question, “Why don’t we have the same reaction to a film like Oliver Stone’s JFK, which goes so far as to use the much-derided filmic ‘recreation?’”

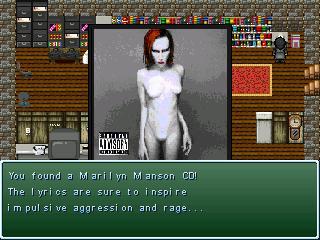

Another editorial game suffering a similar fate was Super Columbine Massacre RPG. This game released roughly around the time that Gus van Sant’s Elephant won the Palme D’or at Cannes; the game, on the other hand, was famously rejected from an indie game festival despite winning the jury prize – showing that even among the art game movement such works were not yet ready to be accepted by some people (this was also the first time many industry outsiders were introduced to the genius of Jon Blow, who withdrew an early build of Braid from the same festival in protest of SCMrpg‘s dismissal). It should also be noted that infanticide was also a popular subject of the saga song of early/mid country music (and true crime novels such as In Cold Blood).

Certainly a big part of all this is a presentation issue: have you ever seen the websites for JFK: Reloaded, 9/11 Survivor, or Super Columbine RPG? Talk about poor marketing and image control. Gus van Sant’s career is particularly important to understanding this aspect of artistic creation. From among all the members of the New Queer Cinema, only van Sant and, to a lesser degree, Todd Haynes have managed to build lasting careers on the edge of the mainstream film industry. They do this by mixing up the topics of their work and tireless promotion at festivals – something aspiring documentary or editorial game developers can learn from.

Of course, there’s no reason that the evolution of videogames as an artistic medium will follow the rules set by previous media. Ian suggests that documentary game developers can simply build on the reputation of documentary film in order to gain leverage as a shared genre–as opposed to a disparate medium. In any case, I hope that I’ve shown that we have reason to believe that games dealing with serious issues will not always remain self-funded projects on the far boundaries of the games industry. Strangely enough, popular reception of these games might rely less on their own intrinsic value than on the increased cultural cache of mainstream games in the coming years.

What an accident. Just today I have been poundering about what problems a documentary game might cause. Excuse me as I go off on a tangent: For example, it’s perfectly ok to do a documentary about McDonalds or WalMart. Could you do a documentary game about Pokémon? I mean a game that is about kids playing the game Pokémon. How would you do that? Would you show footage of Pokémon. Would you maybe even introduce gameplay elements of Pokémon? Would it be ok for Nintendo to sue you for that?

Well you can’t copyright game mechanics in the United States. You can only copyright images and names. So you could essentially make a game about the Pokemon craze from within a game that plays a lot like Pokemon. For instance, a game where your character traps children in little balls by beating them down with advertising messages and lulling them to sleep with plush toys would probably be kosher.

Also, as long as you’re not running ads on a website where you host one of these games usually you’re safe under some kind of artistic non-profit freedom thing, I think?

Well, sure the mechanics are safe but if you wanted to really document (instead of comment on) the Pokémon craze you would need to show or at least name the Pokémon. You could come up with a substitute for the Pokémon your own “fake” Pokémon but that wouldn’t be a documentary anymore, wouldn’t it?

I mean even the name “Pokémon” is technically a registered trademark (as each individual name of every goddamn Pokémon is). It would be difficult to even spell it out that the game is a documentary of “Pokémon”.

I wonder if any such thing as a documentary game can even exist. Movie documentaries work because the medium itself is about capturing bits of reality by filming them. In a way, every movie is a documentary. Games are different. They are at best man-made simulations of reality which are (as every simulation is) incomplete and therefore always an interpretation. This would mean that in a strict sence there can be no such thing as a documentary game because the game’s relationship to reality is heavily mediated. The only way I see for games to become more capable of being documentary is if we develop technologies to directly capture 3D environments and convert them into interactive experiences – kinda like Holodeck.

I think your view of documentary filmic reality is a bit naive. You’ve heard the controversy over Nanook, right? Most early documentaries were so fabricated that there had to be entire movements in the field to combat them. Even now, you get people like Michael Moore who play pretty freely with sound bytes and timelines.

Galloway does a pretty decent job explaining the difference between “realism” in games and “photorealism.” True realism just means adequately expressing a system or thought (photorealism would be what you want, an exact 3D replica of a space).

There are already tons of documentary games, which Cindy Poremba and Ian Bogost attempted to categorize a few years ago. I’m not really worried about their ontological status; I’m more into understanding why they haven’t become more popular.

But yeah the problem you state with a doc game about Pokemon stands. Paolo Pedercini got away with it with his McDonald’s game though (I mean, the Golden Arches are trademarked), so there’s gotta be some way around the problem.